Conundrum of freewill

Oct 25, 2020

A few days ago, I was having a conversation with a friend about the passing away of a famous playback singer S.P.B. One of the gems of the south indian music industry; a 74 year old veteran. He is one of my favourite playback singers.

We were talking about this one song called “உன்னை நினைச்சேன் பாட்டு படிச்சேன்” (I thought about you and I sang!) from the tamil movie ‘Apoorva Sagodharargal’. The lyrics were penned by Vaali; a celebrated poet in tamil. We were appreciating the below lines from that song,

“ஆசை வந்து என்னை ஆட்டி வைத்த பாவம்

மற்றவரை நான் ஏன் குத்தம் சொல்ல வேணும்”

My desire for your love tortures me

Why should I blame others, for that desire was watered by my own fate

“கொட்டும் மழை காலம் உப்பு விக்க போனேன்

காற்றடிக்கும் நேரம் மாவு விக்க போனேன்”

(The below lines are a beautiful poetic depiction of futile actions done out of desire)

I went to sell table salt during a rainy season,

And went to sell flour during a heavy wind

This entire song is about a protagonist Appu’s unreciprocated love for a woman named Mano. Now, Appu, being a dwarf by birth, did not evoke any love interest from Mano, who had fallen for another guy. Is Appu right in blaming fate for the one sided nature of his love for Mano? Did he really have any control in what he felt?

Let’s first start by questioning the origin of thoughts. Thoughts are perceived as abstract entities, which are produced in an actual physical machine; like the brain. And the brain, being a physical entity, is still bound by the laws of physics; at least by the ones that we understand.

Imagine that you are in a supermarket and you are about to choose between buying apples and oranges. You might think thoroughly about your dietary preferences, the fruit stocks at your home, your family's preference, etc and then choose one or, you might even make a blind “spontaneous” choice.

But If you ask yourself, “did I make the final choice?” You will mostly give a strong “Yes”. If you probe deeper, you might give some points, most of which can be reduced to an variation of the following reason,

“Because I could have very well chosen oranges instead of apples i.e I could have acted differently so, it feels like I made the choice; ”

But is that really the case? Studies have shown that there is a time difference between the instant when the brain decides on something and the instant when we are actually aware of it. In our example, there is a time difference between the instant when the intention of buying apples over oranges arrives in your brain and the instant when you became aware of this intention. It seems as if our thoughts are bubbling up from our subconscious and once it breaks into the fabric of our consciousness, it feels like it was us who had that thought. If that is the case, then isn't your feeling, of actually deciding this choice, an illusion? You can still argue that your subconscious (being part of you) made that choice for you. But we only perceive the bubbles when they appear over the fabric and not the origin or formation of those bubbles i.e we see only one side of the fabric, we don’t get to see what goes behind the fabric of awareness (consciousness) deep within our subconscious. So if your subconscious makes that choice for you, how can you prove that it is really free? Can your subconscious make a different choice, given the same options?

Determinism says otherwise. Determinism says that all the events in the universe are deterministic i.e you hit a football, it will fly, abiding by the laws of physics. By Determinism, if you rewind the universe as a whole, particle by particle without any change to the same exact state when you chose apples over oranges, you would make the same choice of choosing apples every single time, even if you do this a trillion times. There would be no variation in it. It will be purely deterministic.

Now consider this, If we know the right parameters of the football, we can predict where it will land. Can that be said about our own thought machines too? After all our brain is merely a biochemical machine that is governed by those same laws. Think about it at least for a minute; why should it be exempt from those same laws? Is there anything which makes it different?

Epicurus, who came one generation after Plato, proposed a new way of thinking which opposed Platonism. He emphasised that all the materials in the world are made of atoms and hence there is no such thing as 'souls' and when we die, we simply cease to exist. He proposed that atoms, although behave deterministically, occasionally (randomly) they perform a “swerve”. He did this to introduce randomness, because he wanted to explain and retain the notion of freewill among us. He believed that since living things are also made of atoms, without this randomness, there would be no other explanation to freewill as everything (including us) would be deterministic and hence not free.

Almost two millennia later; in the 20th century, we stumbled onto quantum mechanics (which, as per our current understanding, is intrinsically probabilistic - opposite of deterministic), which compatibilists (persons who believes that the notion of both determinism and freewill are compatible with each other i.e they can co-exist) use as one of the arguments to explain freewill.

But both of these explanations still explains freewill with the help of an observed randomness in the universe. They bank on the notion that there exists some randomness inside the atoms and particles that makes us, and because of this randomness we are not deterministic, and that we are indeed free to make a choice for ourselves and so we can affect the deterministic causal chain of the universe via this randomness. But, how does randomness explain the “free” in freewill? Consider the same supermarket example, now instead of thinking and deciding, you flip a coin to make that choice. The outcome of that is probabilistic (random), do you then agree that it is really you who made that choice? Despite it being based on the outcome of a random process on which you have no control over? Most of you won’t, then how different is this from the randomness happening inside your brain? If you imagine your brain doing a billion or a trillion coin-flips-like random decision making events to make a decision, then where is the notion of freedom here?

Hard determinists (persons who believe that freewill and determinism doesn’t go hand in hand) say that these seemingly “free” thoughts, that pops up above our fabric of subconscious into our conscious, is merely a result of a set of biochemical processes (which are deterministic processes) that goes inside our brain.

Even if our thoughts are not caused and are arising randomly (indeterminism), then it raises the question of, are there really such a thing as a truly stochastic event or process? Can randomness that we perceive merely be relatively indeterministic? You flip a coin and we believe that there is no way of predicting what will be the outcome of it. We believe that it is random, stochastic, probabilistic but is that really the case? Does true randomness exist? This is for another topic.

In either case, are we responsible for our actions and choices? Our entire judiciary and moral code is predicated on this notion, that a murderer who was found to be guilty, could have chosen to act differently but he/she didn’t and hence they are responsible for their actions.

Let me introduce to you, the story of a 40 year old man. This man was living a happy life, he was married and had a step daughter too. He was initially a corrections officer who later went onto to complete his master’s in education and become a school teacher. All was good. Then during the year 2000, he was kicked out of his house and was later arrested for making untoward sexual advances towards his own stepdaughter. It was later found that he was also collecting porngraphical material related to children and this concluded that he was a paedophile. A judge sentenced him to a sexual rehabilitation program with the condition that if he failed in the program, he would be imprisoned.

Understanding the consequences, he attended the rehabilitation program but he still asked for untoward sexual favors from women staff at the program center. Naturally, He failed the program and was about to be imprisoned. A few days before his jail time was about to start, he complained of a headache and his inability to balance himself when standing up. He was taken to an emergency center where to the surprise of his doctors he still retained the same behaviors of asking sexual favors from those women he encounters, among other physiological changes like losing his bladder control, his gait, etc.

The doctors who examined him, discovered a tumor in his brain which interfered with his orbitofrontal cortex, the part of the brain which is known to be the center of impulse control and which governs social behaviors. On removal of the tumor, his obsession was seemingly gone only to return later when the tumor emerged again. Once it was removed again, it went away for good. After completing the rehabilitation program successfully, he went back to live with his wife and his stepdaughter.

Now, this evoked a moral debate among doctors, sociologists, humanitarians and philosophers as to where should the blame lie for his actions? Had this been a case where there was no tumor involved, it would have been no brainer for most people, the answer would have been to put the responsibility on him.

In the case of tumor being involved, comptablists point out that, though the universe is deterministic and he had no control over the tumor, he was still responsible for his actions because it was his tumor; his own particles, which caused his actions.

If we think about it, how far can we take this argument? If you are indeed responsible for all of your actions, consciously or otherwise, just because those particles or atoms which caused the action lies within you, then are you also responsible for the plethora of microorganisms that lives inside you? They might not share a DNA with you, but some of those are still part of your system of life just like that tumor was with that 40 year old man.

The answers to this might depend on problems like Mind-Body dualism, The problem of personhood and identity, etc. What or who or when an entity is a person? What and where your identity is? What makes you, you? The definition that we attribute here, will have some serious implications on our moral and legal frameworks.

For example, consider the case of abortion. How can we justify the acceptance of a mother choosing to terminate the life of a fetus growing inside her? This is a moral debate that is still ongoing. If a fetus is a person, do they have a say in whether they live or not? On the other hand, how can we justify that killing of a baby (Infanticide), after it is born, is wrong? At what point of time in its life, does killing it becomes infantacide and not abortion? When does the fetus gain personhood?

Some people have proposed what is called 'The gradient theory of personhood'. It explains the question of whether an entity is a person or not, by giving a variable value (or scores) of personhood to an entity over its lifetime. In this way, it says that a fetus starts by having a little to no personhood and gains more personhood as it progresses in time.

It also explains the common practice of why we don't punish or perform judicial trials on children in the same way we carry out a trial on an adult. Humans have the most developed prefrontal cortex among all the animal species that we know of and our current understanding of biology tells us that the prefrontal cortex of a child will not be fully developed before it reaches a certain age.

In the same analogy, Determinists have answered these ethical dilemmas, like that case of the 40 year old man, by correlating our responsibility to our level of control or what I'd like to call 'The gradient notion of control'. The more control we have, the more responsibility we have. As Uncle Ben in Spiderman said "With great power comes great responsibility". By this, it means that the 40 year old man had no control on his tumor and hence his responsibility towards his actions should be minimal.

Let’s take a look at the tale of Oedipus. In one version of the story, When Oedipus was born to King Laius of Thebus, it was foretold by an oracle that he would kill his father (The king) and marry his mother (The queen). This thought is absurd to most of us and even to Oedipus himself (as we see later in the tale). Oedipus’s father, worrying about this, abandoned his newborn son in a forest hoping that he would die (a form of infantacide). The tale tells that “Fate” had “other plans”. A passerby shepherd, who found the abandoned baby Oedipus, took him to the King of Corinth who adopted him to be his son. When Oedipus grew up to be an adult, he came to know of his foretold predicament by another oracle. Oedipus, who was unaware that he was adopted, decided to resist this fate by staying away from his adopted parents permanently. He moved away from Corinth in order to never see them again. Later in his life, the tale goes on to tell us that, in a fit of provoked rage, he killed a man. He then later came across a sphinx that lived near the city of Thebus. It posed a riddle to all the people it encountered and if they failed to answer it, it devoured them to death. Obviously people were not happy about it. When Oedipus answered the riddle correctly, the sphinx was so distraught that it killed itself. People rewarded him by offering to marry their queen to him. They did marry and had four children. Later in his life, he learnt that the man he killed is none other than his birth father and the queen he married is none other than his own widowed birth mother. His birth mother killed herself and Odeipus blinded himself when they learned about this truth. It is indeed a tragic tale to hear. People often cite this tale as an example of how human actions and choices are powerless against fate. Both Odeipus and his birth father believed that they could alter their foretold fate. But “apparently” fate worked its course despite their efforts.

One of my favourite movies; “The adjustment bureau” tells a tale of two people, who believed in their ability to overcome their supposed fate. The notion runs parallel to the tale of Oedipus but with a different outcome.

Can Determinism and Fatalism be conflated? Determinism should not be confused with Fate or Fatalism. There is a difference between Determinism and Fatalism (or pre-determinism). In other words, there is a difference between predictable and predicted. If the universe is indeed pre-deterministic, then what Fatalism says is that everything is predisposed to happen, starting with the Big Bang. Then are we really in control of our life, even if we do, how much control do we possess? If we don’t have any control, what sort of consequence will it have if such notions are widely accepted?

There have been studies in which a group of students who were imbibed with ideas of some form of determinism, found to be more prone to indulge in cheating on their academic tests. This is far from a huge scale societal disruption but when people undergo what is called “resignation” (when they submit to fate), it has a potential to wreck our current order and cause chaos. This resignation is a form of psychological bypassing.

Let me tell you the story of a shipowner in the colonial era. One of the ships he owned was ought to set on journey from North America to England. Being the owner, he knew that the ship was old and in dire need of a overhaul but he still chose to send the ship on its journey. The ship never made it to England and the sailors, in it, died. He was sad and was filled with guilt, which is to be expected. But what some philosophers argued was that, even if the ship had-had made it to England, he would still be filled with guilt because he failed to fulfill his epistemic responsibility.

Epistemic responsibility is a responsibility that arises out of a person's level of cognition and knowledge. In simple words, a school bus driver has more epistemic responsibility than a caretaker in the bus, a country’s head of state has more epistemic responsibility than his/her subjects, etc. Imagine a doctor and a chef finding an injured person lying down on a roadside, fighting to stay alive. Here, the doctor has relatively more epistemic responsibility than the chef, to try and save that person’s life. This is because the doctor here possess relatively more knowledge (or access to it) and a better level of cognition in treating an injured person.

We all have some level of epistemic responsibility. For instance, imagine you are driving a car on a road and you want to take the next turning into another road; you have both a legal (at least in most nations) and an epistemic responsibility to indicate to other drivers that you are indeed turning (turn on the indicator light and perhaps even give a small level of horn when making the turn).

Some years ago, during my college days there was debate in my classroom on some topic which I don't remember but I remember my answer to the question which was posed "What is luck?".

I thought about it for some time, before giving my answer "Luck is the collective impact of society on oneself". Of course, this was back in time. I would better rephrase it now as "Luck of an entity is the collective impact of the state of the rest of the universe on that entity".

So, we all play a factor, it might be a lot or a little, in everything else in the universe. This might sound as a variation of the butterfly theory (Chaos theory). So, whether we like it or not, we all are impacted by the epistemic responsibility of each other. That is the understanding I had during my college days when I tried to answer the question of what is luck.

When I began exploring the notions of freewill; arguments supporting it and the arguments opposing it, there was an inception of questions in me like “what is indeed the truth? Am I in control of my destiny? How much control do I possess?” and it made me realize that I need to philosophically re-evaluate my beliefs and perspectives on life, if not I might drift far away from the truth.

I’d like to tell the story of Descartes. He took a journey to understand the true nature of things, he started to question everything. He argued that in order to figure the truth out, one needs to start with a clean slate and think critically about every one of their beliefs. He gave an example of an apple basket. Imagine, you bought a basket of apples and you need to ensure that none of the apples in it are rotten. To ensure that you do this properly, he argued that, first you need to empty the basket and examine each apple separately before placing them in the basket. This is because he believed that a rotten apple might have an impact on a healthy apple while you are evaluating. Likewise a false belief, which is keeping us away from the truth, might impact our other beliefs.

A few years ago, I was watching a series called 'The covert affairs'. In one episode, the female protagonist will try to convince another character in the series to do the right thing. He will refuse and put the blame, for his inability to do the right thing, on fate. To which she counter-argued saying, "Fate is what happens to us, Destiny is what we do in-spite of our fate".

I resonated with it very well as it reinforced one of my notions in life very strongly; “தீதும் நன்றும் பிறர்தர வாரா” from Purananuru, one of the eight anthologies of The Sangam literature. What it means is that “Nothing good or bad comes from outside but only from inside”. It resonated with me very well because, I personally believe it is good to take responsibility for the things that happens to me, in this way, instead of whining, I get to improve myself with time; which is another notion that I very strongly believe in; “Not enjoyment, and not sorrow, Is our destined end or way; But to act, that each to-morrow Find us farther than to-day.” from ‘The Psalm of Life’ written by H.W. Longfellow.

Though we all share an epistemic responsibility to figure out the truth, not a lot of us have the timespace or energy to think, using the same framework as Descartes. It would be difficult to do so properly. A medical researcher; questioning and expanding our current understanding of biology, might posses a belief that if they press their car’s gas pedal, it will move. They, or for that matter any non-engineer, might not necessarily have a deeper understanding about the mechanisms of a car. Not all people have time to assess and re-evaluate each and every aspect of the car to verify that belief for themselves. It is not pragmatic to do so. I too have had guilt about the fact I am believing in things without probing deeper about it and not being as thorough as Descartes. After all Philosophy is all about not taking anything as given and questioning everything to figure the truth. That is why philosophical debates have been raging on, not for centuries but, for millennia. The questions that we are discussing now, have been asked by people who lived those many years ago. The more I think, the more I believe that I have indeed adopted more of a pragmatic notion in my day to day life. I choose the beliefs which works for me well and I do question some of them from time to time, especially the ones which interest me and I will explore those myself. But I never consciously question all of them because it will be difficult for me to do so. However, I still keep an open mind about them because there are other people who are helping me in questioning mine just like I am helping them in questioning theirs. I believe, We as a humanity have adopted the strategy of divide and conquer as one of our approaches to truth and philosophy has formed as one of our formal argumentative frameworks.

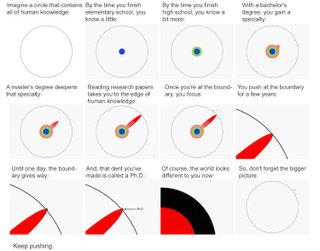

Once a student asked a professor, what is a PhD? The professor illustrated it as follows

My goal is to try and keep pushing and contributing to this mission how much ever I can, no matter how small or big it is.